When James Cameron’s Titanic premiered in 1997, it became a cinematic spectacle and a cultural phenomenon. While the film is often remembered for its groundbreaking visual effects, massive box office success, and the unforgettable image of Jack and Rose at the bow of the ship, its more profound legacy lies in how it reshaped public understanding of the historical Titanic disaster. By framing the tragedy through a deeply emotional love story rather than focusing on the ship's technical failings or the crew's actions, the film transformed a largely male-dominated historical narrative into one that resonated with a much broader, more diverse audience. It opened the gates to new forms of historical inquiry, allowing the Titanic’s legacy to become a more human, emotional, and inclusive story.

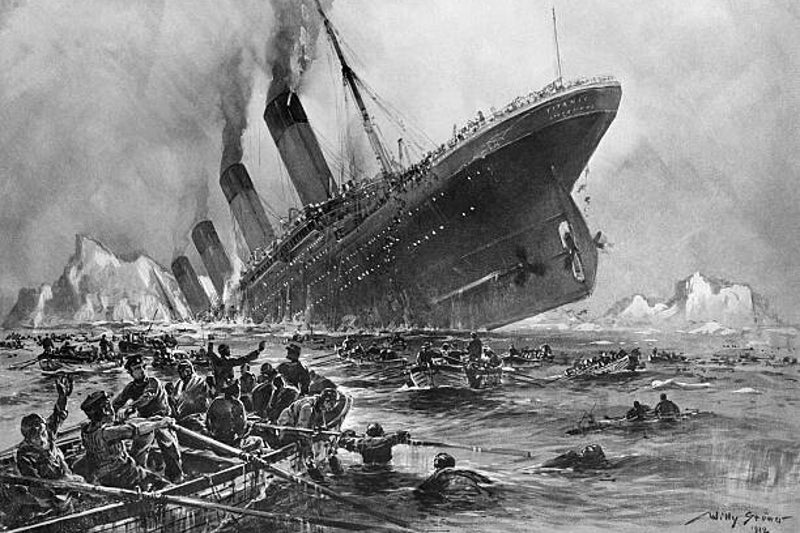

Before the film’s release, the study of the Titanic had been primarily the territory of maritime historians, engineers, and naval enthusiasts. These communities often centered their research around the ship’s construction, its alleged design flaws, and the various failures in communication and navigation that led to its demise. The focus remained mainly on the mechanics of the disaster, how the iceberg was struck, why the hull failed, how the ship broke apart, and how lifeboat protocols were botched. It was a domain governed by blueprints, ship manifests, and procedural autopsies. And within that world, the most dominant voices were typically men, many of whom came from engineering or military backgrounds.

Cameron, however, approached the story not as a maritime scholar but as a storyteller fascinated by the human experience. While he meticulously researched the technical details and strove for historical accuracy in the depiction of the ship, he made a bold and significant choice to center the film around the fictional romance between Rose DeWitt Bukater and Jack Dawson. That narrative decision did something that decades of documentaries, shipwreck studies, and survivor accounts had not. It gave Titanic a soul. Suddenly, audiences were not just observing a tragedy from a distance. They were feeling it. They were emotionally entangled in the lives of two people caught in a moment of brief, intense love, interrupted by a catastrophe that took over fifteen hundred lives. The iceberg was no longer just a maritime hazard; it became the villain that separated two lovers, a force that interrupted dreams, severed futures, and left behind silence and cold.

This shift toward emotional storytelling had profound consequences. It brought women into the Titanic story in a way that had not been seen before. The narrative focuses on Rose, a young woman trapped in the rigid expectations of her class and gender, and her journey toward personal liberation resonated deeply with female audiences. Her story symbolized resistance, agency, and growth, turning the Titanic into a stage for tragedy and transformation. For many women who may have previously seen the Titanic disaster as the realm of technical jargon and stoic historical analysis, the film created an entry point rooted in empathy and identification.

As a result, the field of Titanic scholarship began to expand. Women started writing books, participating in online forums, attending exhibitions, and conducting their research into the lives of passengers and crew. Rather than focusing exclusively on the elite, many amateur and professional historians started investigating the experiences of steerage passengers, immigrant families, ship workers, and musicians. The humanity of those on board became just as important as the steel plates and rivets that held the ship together. Emotional engagement became a legitimate form of historical inquiry, and public history, fueled by the accessibility of the internet and the community-building power of fan culture, began to shape how Titanic was remembered and studied.

Museums and Titanic exhibitions around the world noticed the shift. Attendance skyrocketed in the years following the film’s release, with a notable increase in women and younger visitors. Many came not only to view artifacts but to learn about the people behind them, often seeking the names and stories of those who had previously been little more than statistics. Memorials grew more personal, less about the enormity of the loss and more about the lost individuals. Titanic-related literature expanded beyond technical analysis to include memoirs, biographies, feminist readings, and psychological portraits. Where once the study of Titanic had been about what went wrong structurally, it began to include questions of what it meant emotionally, how people lived and loved, how class shaped fate, and how memory preserves or forgets.

The film also helped frame Titanic as more than a moment frozen in time. It began to be seen as a story about modernity, inequality, and the illusion of control. Rose’s survival and choice to abandon her privileged world suggested that the Titanic was not just a cautionary tale about nature’s triumph over human arrogance. It was also a parable about personal transformation and the capacity for rebirth amidst ruin. These themes gave the Titanic resonance far beyond historical circles, embedding it in conversations about gender, class, trauma, and resilience.

In the years since the film’s release, Titanic studies have continued to evolve, shaped by discoveries, technologies, and perspectives. Yet it is undeniable that James Cameron’s film served as a pivotal cultural moment that democratized interest in the Titanic and redefined how the disaster is understood. By choosing to tell a love story within the framework of historical tragedy, he shifted the center of gravity from the mechanics of sinking to the hearts of those who went down with the ship. In doing so, he changed how we remember the Titanic and who gets to be part of that memory. The Titanic became not just a sunken ship but a vessel of human meaning, one whose legacy is now carried by a broader and more emotionally connected public.

Add comment

Comments