British Israelism, a belief system that emerged in the early nineteenth century in Britain, is rooted in the intriguing notion that the British people are the direct descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. This theological claim, initially on the fringes of Protestant esoterica, proposed that Anglo-Saxons, and by extension other Northern Europeans, were the true Israelites. Over time, this theory, a fusion of amateur biblical scholarship, racial identity, and historical conjecture, evolved into a more coherent ideological movement that transcended religious speculation. By the late nineteenth century, it had become a widely circulated theory among certain Christian groups, providing spiritual validation for imperial ambition, cultural supremacy, and national pride. It presented Britain’s global reach not as a product of historical circumstances but as the fulfillment of a biblical destiny.

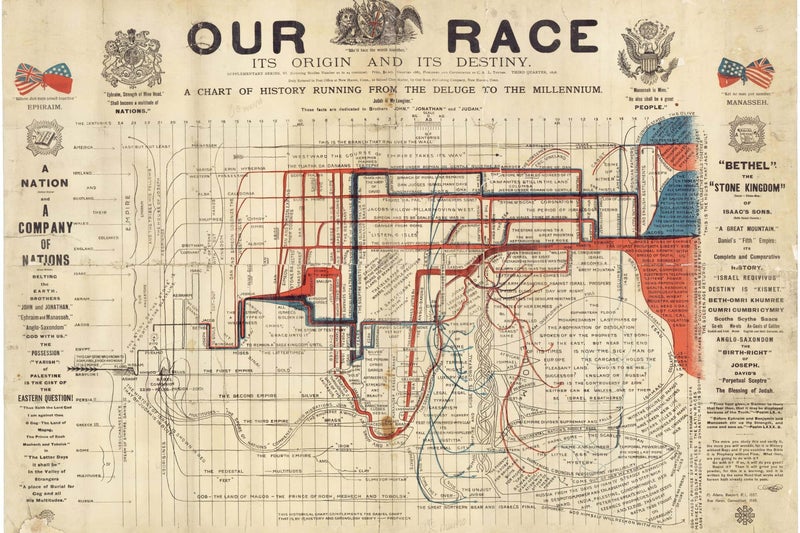

The intellectual foundations of British Israelism were laid by figures such as Richard Brothers and John Wilson. Wilson’s 1840 work, Our Israelitish Origin, offered linguistic and cultural arguments meant to trace the ancestry of the British back to the Israelites, and his ideas inspired a host of successors. One of the most influential was Edward Hine, who infused the movement with an explicitly nationalistic and imperial character. Hine argued that Britain’s dominance in global affairs was not merely a matter of military strength or economic ingenuity but rather the direct result of divine favor. He linked the British royal family to the biblical House of David, claiming that the British Crown was a continuation of the Israelite monarchy. This theological narrative resonated with many Victorians, who viewed their nation as a moral and spiritual force in the world. It reinforced a sense of cultural exceptionalism and racial superiority cloaked in the language of providence.

Although British Israelism remained marginal in theological terms, it had a significant impact on political and cultural spheres, not only in Britain but also in the United States. In Britain, it attracted a diverse group of enthusiasts, ranging from lay theologians and clerics to imperial officials and aristocrats, some of whom took its claims seriously enough to influence public speeches and imperial ideology. It also inspired the establishment of various societies and publications dedicated to disseminating its message. However, the theory did not remain confined to Britain. It was quickly exported to the United States, where it evolved into a distinctly American variation often referred to as American Israelism, influencing a new set of thinkers and shaping a different cultural landscape.

The transformation from British Israelism into American Israelism was not abrupt but instead unfolded gradually as the theory crossed the Atlantic. In the American context, the themes of divine election and national purpose found fertile ground in an already flourishing culture of religious exceptionalism. Many American Protestants in the nineteenth century believed that the United States was a new Israel, a nation chosen by God to lead the world into a more righteous future. This idea of manifest destiny aligned easily with the core tenets of British Israelism, and American religious thinkers adapted the theory to fit their own historical and racial narratives. Where British Israelism had emerged alongside the justification for empire, American Israelism developed alongside the ideology of westward expansion, industrial domination, and the growing self-image of the United States as a redeemer nation.

American Israelism retained the essential theological claim that white Anglo-Saxon Protestants were the true descendants of ancient Israel. Still, it placed greater emphasis on the United States as the geographical and spiritual center of this divine lineage. The British monarchy faded into the background, and in its place rose the idea of the American Republic as the new covenant nation. The theory became a way for American Protestants to reconcile their religious identity with national pride, often reinforcing racial hierarchies and xenophobic attitudes under the guise of biblical prophecy. Over time, the racial component grew more pronounced, notably as American society underwent significant demographic and political shifts during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. What began as a theologically infused national mythology would eventually harden into the racialized doctrine known as Christian Identity.

Christian Identity, a religious movement that emerged from British Israelism and American Israelism, took the principles of American Israelism and radicalized them. By the mid-twentieth century, this belief system had become deeply intertwined with white supremacist ideology. It no longer merely claimed that Anglo-Saxons were Israelites. It asserted that Jews were not Israelites at all but imposters and, worse, the descendants of Satan or Edom. In this theological inversion, white people became not just the inheritors of Israel’s promise but the only true children of God, while Jews and non-whites were cast as enemies or subhuman. Christian Identity rejected the inclusive messages of mainstream Christianity in favor of a dualistic worldview in which the world was divided into godly white Israelites and demonic others. These beliefs provided spiritual justification for segregation, racial violence, and political extremism. Groups like the Ku Klux Klan, Aryan Nations, and various paramilitary militias adopted Identity theology as both creed and call to arms.

In Britain, British Israelism, while never taking on the virulent, racially militant tone that it acquired in the United States, retained some cultural influence well into the twentieth century, especially among certain Anglican circles and reactionary political groups. Although it mostly faded from public view after World War II, its ideological legacy endured. Far-right movements in Britain have echoed its themes, especially the idea of a divinely ordained British identity under threat from immigration, secularism, and globalization. While these groups do not usually reference British Israelism explicitly, its residue remains in their narratives of national purity, racial heritage, and spiritual decline.

In the United States, even as Christian Identity declined in organizational coherence, its ideological tenets continued to circulate among far-right extremists. It helped shape the worldview of white nationalists, neo-Nazis, and conspiracy theorists who continue to view history as a cosmic struggle between a chosen white race and an array of racial and political enemies. The internet has only accelerated the spread of these ideas, often divorced from their original religious language but retaining the exact structure of chosen identity, divine struggle, and apocalyptic resolution. It is in this context of ideological proliferation that an ironic parallel has emerged from a completely different racial and social experience: the rise of the Black Hebrew Israelite movement, a religious movement that claims that African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans are the descendants of the ancient Israelites.

The Black Hebrew Israelite movement, like its white supremacist counterparts, is rooted in the claim that specific people are the true descendants of ancient Israel. But in this case, the chosen people are not Anglo-Saxon Protestants but African Americans. This belief emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a period marked by intense racial oppression, legal segregation, and cultural exclusion. For many Black Americans, mainstream Christianity offered little comfort or dignity in a society that denied their humanity. Some turned to alternative religious traditions to reinterpret their place in biblical history and reclaim a sense of purpose. In doing so, they encountered and reworked the theological scaffolding of American Israelism.

Early figures in the Black Hebrew Israelite movement, such as Frank Cherry and William Saunders Crowdy, drew directly from American Israelist writings. These men had encountered versions of British Israelism that had circulated widely through American churches, tracts, and newspapers, and they adapted the core idea of lost Israelite ancestry to a Black American context. Instead of identifying Anglo-Saxons as the true Israelites, they identified the descendants of enslaved Africans. The language of exile, covenant, and redemption resonated powerfully with communities that had experienced centuries of bondage, violence, and systemic injustice. The result was a theological framework that affirmed Black dignity while also offering a radical reinterpretation of history.

Many Black Hebrew Israelite groups emphasized spiritual discipline, self-reliance, and separation from mainstream American society, but as with other identity-based religious movements, different factions developed divergent views. Some were peaceful and religiously focused. Others adopted militant rhetoric, antisemitism, and anti-white attitudes. The most radical groups argued that Jews were not the real Israelites and accused them of stealing a divine heritage that rightfully belonged to Black people. In this sense, their worldview mirrored that of Christian Identity groups, though their historical narratives and racial identities were opposed. Both movements claimed the status of God’s chosen people. Both demonized Jews as pretenders to a sacred lineage. Both interpreted contemporary history through a biblical lens of exile, judgment, and eventual triumph.

This ironic convergence of structure reveals the enduring power of the original theological model developed by British Israelism. A religious narrative initially created to reinforce white Anglo imperial confidence became a framework that was later inverted and adopted by some of the very people it once excluded. The theological scaffolding remained intact. Only the actors in the story changed. The common elements persist. There is the belief in a lost identity recovered, a divine covenant restored, a hostile world to be overcome, and an apocalyptic reckoning in which truth and justice will prevail.

The story of British Israelism and its ideological progeny is not just about theology. It is about how ideas move across borders and centuries, how social conditions reshape them, and how they offer meaning in times of crisis. Whether in the form of imperial confidence, white nationalist paranoia, or Black religious reclamation, the underlying appeal is the same. These narratives promise that suffering is not meaningless, that one’s people are not forgotten, and that history is not random but divinely directed. They offer identity, purpose, and destiny to those who feel alienated from the present and uncertain about the future.

Understanding this lineage is crucial not only for tracing the intellectual history of religious nationalism but also for grasping the deeper psychological and cultural currents that make such ideologies enduring. British Israelism began as an obscure belief about ancient tribes and national lineage. It became a theological justification for empire, then a racial doctrine of exclusion, and finally, a mirror in which both supremacists and the oppressed could see reflections of divine election. In each iteration, the core mechanism remains the same. It is a story that fuses identity with sacred history, transforming myth into a political conviction and personal alienation into cosmic significance. It is a story that continues to shape modern extremism in subtle and dangerous ways.

Add comment

Comments