The rise of Donald Trump as a dominant figure in American politics cannot be understood simply by pointing to racism, xenophobia, or media manipulation. Those explanations, while not irrelevant, are insufficient. Something more profound is happening. It extends beyond cable news and Twitter, reaching into the daily lives and unmet needs of millions of Americans. To truly grasp why so many lower-income voters, many of whom once reliably voted for Democrats, are now turning to Trump, one must explore the psychological architecture that drives human behavior. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs offers a powerful lens through which to understand this shift, illuminating how class, insecurity, and political alienation are reshaping electoral loyalties in the United States. The urgency of the Democratic Party's need to reconnect with these voters cannot be overstated.

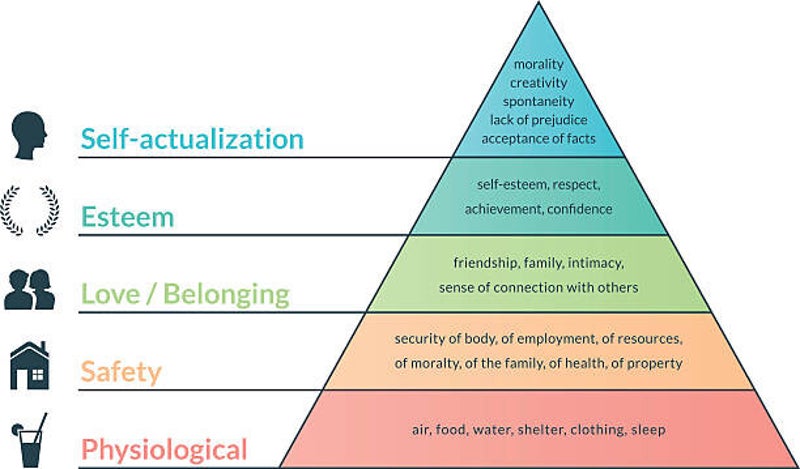

Maslow’s theory suggests that human beings are motivated in stages, beginning with the most fundamental physiological needs, such as food and shelter, followed by the need for safety, then love and belonging, esteem, and finally, self-actualization. When people are struggling to feed their families, pay the rent, stay healthy, or feel safe in their communities, they are not primarily concerned with higher-order ideals. They are focused on survival. They are looking for stability. They are looking for someone who sees them and understands the world they live in. They are not interested in academic abstractions or symbolic gestures. They want real change they can feel.

Over the past several decades, the Democratic Party has gradually shifted its focus from lower-income voters to the professional and managerial classes. This realignment has had significant consequences for the way the party communicates, the priorities it emphasizes, and the people it serves most visibly. College-educated voters now comprise a growing share of the Democratic coalition, and as their influence has increased, so too has the party’s focus on issues that resonate with people whose material needs are met mainly. These include climate policy, diversity and inclusion, voting rights, criminal justice reform, and other vital causes that speak to the values of progress and equity. But these are also issues that reside higher up in Maslow’s pyramid. They require a baseline of economic and personal security to become meaningful political priorities. When the Democratic message is built around these themes, it often fails to connect with voters who reside near the base of the pyramid, those for whom each month is a struggle to make ends meet.

This disconnect has created a growing political vacuum that figures like Trump have been able to fill. He did not need to offer detailed policies or technocratic plans. What he offered instead was emotional recognition. He spoke to the people who feel ignored. He told them that their communities mattered, that their jobs mattered, that their sense of belonging to a nation with borders and laws mattered. He validated their fear that the world was moving on without them. He positioned himself as a bulwark against elite condescension and cultural displacement. That message, however blunt or cynical, resonated deeply with those whose lives had been destabilized by deindustrialization, wage stagnation, the erosion of union power, and the offshoring of economic opportunity.

Many of these voters once looked to the Democratic Party to protect their interests. They recall when the party stood shoulder to shoulder with organized labor as it fought for wage increases, Social Security expansion, and government programs that provided material support. However, in recent years, many of these voters have observed the party shifting its emphasis toward causes that, although important in principle, seem far removed from the problems they face. They hear debates about pronouns, not pensions. They see college-educated activists on social media debating the nuances of climate discourse while their utility bills are skyrocketing. They watch wealthy urban professionals champion progressive ideals while voting against housing construction in their neighborhoods. They are not indifferent to questions of justice and equality. But they are trying to get through the week.

This is not simply a matter of messaging or tone. It reflects a more profound structural realignment in the American political system. As the Democrats have grown more reliant on the professional class for donations, media support, and institutional power, they have inadvertently allowed their politics to reflect the worldview of that class. This worldview values symbolic politics, rational discourse, and global integration. It assumes a level of security that allows for long-term thinking and abstract idealism. But millions of Americans do not share that experience. They are not attending panel discussions or watching TED Talks. They are working night shifts, navigating broken healthcare systems, and watching their towns hollow out. For these Americans, the Democrats now look less like a party of the people and more like a party of people who assume their problems are already solved.

Trump, for all his flaws, speaks the language of need. He does not appeal to self-actualization. He appeals to the values of safety, belonging, and recognition. His rallies are not policy briefings. They are rituals of collective affirmation, where people who feel unseen in the new American economy come together to be reminded that they still matter. His platform is filled with grievances, but those grievances map onto real insecurities. They are rooted in the very bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy. When people live in economic uncertainty, feel like strangers in their neighborhoods, and see that their work no longer provides dignity or purpose, they are not looking for parties that ask them to understand systemic privilege or support global equity frameworks. They are looking for someone who promises to fight for them. The Democratic Party must learn from Trump's approach and adapt to the needs of these voters.

This does not mean Democrats must abandon their commitment to justice or inclusion. But it does mean they must reconnect those values to the economic and material realities of the people they hope to represent. Climate policy cannot be presented as an elite moral imperative. It must be shown to create jobs and reduce costs. Criminal justice reform cannot be framed only in terms of academic critiques. It must address people’s concerns about safety and stability. Racial equity must be coupled with economic investment in neglected communities, both urban and rural. Democrats must learn to speak again in the language of bread and butter, of factories and farms, of family budgets and community well-being. They must remember that politics is not a debate club. It is a lifeline.

The people turning to Trump are not doing so because they have changed. They are doing so because the world around them has changed, and they are seeking someone who can see it. Maslow’s theory reminds us that politics, like all human behavior, begins at the bottom. It starts with hunger, with fear, with the need to feel safe and recognized. If the Democratic Party cannot once again become the champion of those needs, it will continue to lose the very people who once defined its soul. These voters do not want to be lectured or pitied. They want to be heard. They want to know that their lives matter, that their work matters, and that their future issues are addressed. And they will follow the leader who gives them that assurance, even if that leader offers no solutions, only the promise that they are not alone in their struggle. That promise, simple and powerful, is the foundation of politics. It is also the base of the pyramid.

Add comment

Comments